The element of chance and working with randomized factors are becoming bigger and bigger parts of what I am creating; discovering processes in which these can be integrated are important.

Brion Gysin pioneered techniques of randomness which may seem somewhat obvious, but during the Beat Movement, his “cut-ups” shaped both poetry and visual arts, introducing aspects of uncertainty, and molding them into artistic creations, often resulting in the sacrifice of visual appeal; similar to the “exquisite corpses” of the Surrealists.

Most everything Gysin produced involved chance interactions between man and environment in some sense – the visualizations that occur when using his invention the Dream Machine, or reinterpreting found text into new poems, or taking stylistic cues from writing systems to create script void of any literal content.

Summarizing the many variations he made upon his new techniques would require more space than I allot to myself, but the scope of his work and collaborations testify the ability to transfer Gysin’s ideas into most any media and realm of study.

The only man to receive William S. Burroughs’ respect (Burroughs’ words), Gysin in many ways provided a climate to perform experiments on the human-environment relationship, the relationships between humans, and within human awareness and control.

Brion Gysin & William S. Burroughs: The Third Mind, 1965. From Look Into My Owl’s review of Dreammachine, the Brion Gysin retrospective show.

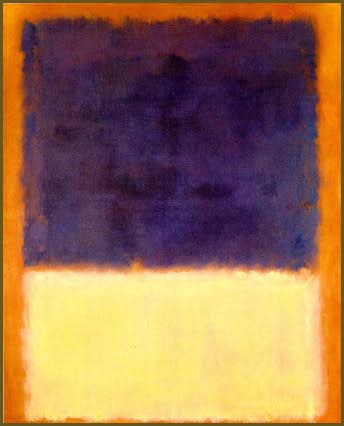

Brion Gysin: Calligraffitti of Fire, 1985. Gysin’s final piece, and one of his few large-scale pieces. From the official Brion Gysin website; provides a lot of examples of his work (paintings, audio, videos), as well as articles discussing him, his techniques, shows, anything.

Brion Gysin: Calligraffitti of Fire, 1985. Gysin’s final piece, and one of his few large-scale pieces. From the official Brion Gysin website; provides a lot of examples of his work (paintings, audio, videos), as well as articles discussing him, his techniques, shows, anything.

Brion Gysin: Calligraffitti of Fire, 1985. Gysin’s final piece, and one of his few large-scale pieces. From the official Brion Gysin website; provides a lot of examples of his work (paintings, audio, videos), as well as articles discussing him, his techniques, shows, anything.

Brion Gysin: Calligraffitti of Fire, 1985. Gysin’s final piece, and one of his few large-scale pieces. From the official Brion Gysin website; provides a lot of examples of his work (paintings, audio, videos), as well as articles discussing him, his techniques, shows, anything.